|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1 bag | 3 in. high |

|

1 bag length | 12 inches long |

| 4 bags | 1 foot high |

|

2 bags (end to end) | 24 inches long |

| 8 bags | 2 feet high |

|

3 bags (end to end) | 3 feet long |

| 12 bags | 3 feet high |

|

6 bags (end to end) | 6 feet long |

| 16 bags | 4 feet high |

|

9 bags (end to end) | 9 feet long |

| 20 bags | 5 feet high |

|

12 bags (end to end) | 12 feet long |

| 24 bags | 6 feet high |

|

15 bags (end to end) | 15 feet long |

| 40 bags | 10 feet high |

|

18 bags (end to end) | 18 feet long |

|

*** Note: see comments on "buttresses" under Wall Length (below) |

||||

Example #1:

Imagine a wall that's 5

feet high and 12 feet long. With bags at 12"

long, you'll need about 12 end-to-end bags to span

the wall's length of 12 feet. This is one "course".

You'll need 20 courses of 12 bags each, one on top

of another, to reach the wall's height of 5 feet. 20

courses times 12 bags each = 240 bags (not counting

bags for buttressing).

Example

#2:

Consider a wall that's 8 feet high and 36 feet long. Each course (row) will have 36 end-to-end bags, and you'll have 32 courses. 36 x 32 = 1152 bags (again, not counting bags for buttresses).

These figures are guidelines. If your wall is 35 feet long, you'd simply dump out one or more bags and use partials. And, again, an alternate way to estimate how many bags you'll need is to look at our calculation page, which again is based on 30 lb bags. If you're filling your bags more (say 4-5 inches high, or 18" long, or whatever) then you'll of course have to make adjustments.

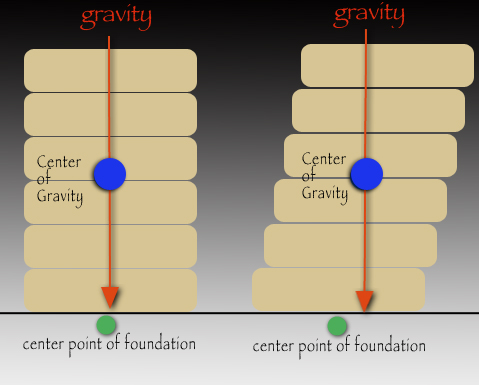

Stability:

It can't be emphasized

enough how important it is to frequently check your

work with a level to ensure that your walls are

vertical as you add courses.

Consider that a 8 foot by

8 foot wall is going to weigh over 4,500 lbs (over

two tons). If the weight is directed straight down,

towards the foundation, your wall (and everything

that's tied to it) will be stable. If your wall is

"off vertical" even just a few degrees, the error

will magnify as your wall increases in height &

you run the risk of the wall eventually failing -

either by shifting (causing cracks throughout your

structure) or collapsing.

With wood, you can make adjustments with shims as you go along. With earthbags, you can do the same with how you lay your bags (a little thicker on one end than the other) & how you use your tamper. Using barbed wire to lock the bags together is recommended up to 2 feet high; over this, you should consider it mandatory.

Wall Length & Buttressing:

Despite whatever care you give to leveling your foundation, and despite the stable 12" width of our dirtbags, you'd be well advised to consider the addition of a buttress every10-12 feet or so for straight, free-standing walls. Emphasis upon "straight"; sinuous walls are more stable.

The rule of thumb is 2:1;

one-foot thickness of buttress for every two feet of

wall height. A 6-foot high wall should have a 3-foot

thick buttress every 10-12 feet. (The hypothetical

36-foot long, 8-foot high wall mentioned above

should have 2 to 3 buttresses, each 4 feet thick,

adding an extra 96 bags per buttress to the 864 bags

estimated, for a grand total of 960.) Of course, the

buttresses should have their own gravel or

rock-filled trench foundation to sit upon so they

don't shift.

Optionally, there are those who have built double-thickness walls (24" thick), and one person even spaced the two walls 6" apart & filled in the gap with packed earth for 30" thick walls. With that wide a footprint, buttressing might be far less critical. But they do look cool and can lend themselves to secondary uses such as benches or planters.

Doors & windows:

When figuring out how many bags you'll be needing, you'll want to factor in the number & sizes of your doors & windows and then subtract these spaces from your total square footage.

Let's say one wall is 10 feet high and 15 feet wide; that wall will be 150 square feet, and - based on our calculations page - will require about 450 bags. If that wall will have a 3x6' doorway and a 2x3' window (18 square feet + 6 square feet = 24 square feet), then that wall will result in being 126 square feet and will require approximately 375 bags... a savings of about 75 bags. (Note that the bags you save here can then be used for benches, planter boxes, covered porches or buttressing - see below.)

You'll be wanting to frame out your doors & windows with wood, and build your bags around the frames. The frames will serve several purposes. The most obvious is providing a guide for stacking your bags & provide something for the bags above the lintels to rest on. They'll also increase the strength of the wall (the sheer weight of the bags pressing against the sides and pressing down will firm up the openings). And finally, the wood will give you something to nail or screw hinges into for doors, shutters, etc.

Speaking of which, we should mention gringo blocks, which are blocks of wood that are the same approximate dimensions as your bags (height & width, if not length). By substituting these in in your wall in place of bags, you'll have a wooden surface to which you can nail or screw shelves or whatever.

Roofs:

Best practice for roofs is to start with installing a bond beam atop your walls. These come in essentially two flavors.

Wood bond beams are just that; heavy wooden beams, tied together at the corners, and well secured to the tops of the walls. Drilling holes in the beams & pounding 18-24" lengths of rebar down into the top courses of bags is a good approach. If you have access to an electric drill & if your bags - once cured - can handle having holes bored into them without splitting, then this will give you a secure bond beam that you can then attach your roof to & have a high level of confidence that it won't blow off in a big storm. You'll want this to be bomb-proof.

Some building codes will call for a cement bond beam. This consists of installing vertical lengths of rebar in your upper courses (especially at the corners), then clamping plywood forms to both sides of your walls, creating a trough all the way around. Once your trough is ready, you'll then pour mixed concrete into the trough to a typical depth of 8-12". The cement will flow around the rebar When it cures, you can remove the plywood forms & you'll have a solid concrete beam that's securely attached to the tops of your walls and into which you can drive bolts to secure your chosen roofing.

Another approach is to crenellate the tops of your walls - like castle battlements - and then lay thick timbers in the openings, spanning the roof. Here in the Southwest, these timbers are commonly 6-12" diameter tree trunks called vigas. You'd want to space your crennelations accordingly so the vigas are a nice fit. After they're in place, you can wedge them so they don't move, and then plaster around them. Once they're in place, you can nail or tie latillas (smaller limbs) at a right angle over the vigas, then finish the roof however you like - wood, thatch, dirt, mud - whatever.

Floors:

The simplest option is a tamped earthen floor. Plastic sheeting covered with tamped dirt will provide a vapor barrier to keep cold, dampness, and critters at bay. Next might be a mud floor a couple of inches thick.

Early settlers in this part of the country, when building adobe structures, mixed mud with ox blood for rock-hard floors (still doing good after 300 years). But you could get away with using clay-rich mud or adding wheat flour or egg whites. Alternatively, you could use the same basic clay-rich mud you use for your bag fill & plaster, polish it smooth after it hardens, and then add a couple of coats of polyurethane, shellac or linseed oil to protect it.

Bricks or pavers used for patios are another option (set these in sand). Cement floors are easy to pour, and then (before it hardens) you can add tile, flagstone or slate, pebbles, beach glass - pretty much anything you like.

Raised wooden floors on studs are also a possibility, and give you the option of utilizing the space underneath for plumbing, wiring, and even storage. You'll want to excavate your foundation before you start building if you're considering this option. If you do this, remember that you'll need to incorporate access to this area (if you have plumbing or wiring). You may also want to consider incorporating some kind of drainage in the event that you have plumbing failures, a large spill inside, rainwater getting in or flooding. If you have space under your floors, installing an economical bilge pump (12 volt) or sump pump (120 volt) is a good idea, even if you never have to use it.

Plumbing, wiring, attachments, etc:

Since the face of your stacked & tamped bags are scalloped (rounded with crevices in between), those crevices can be ideal for running pipes, conduit or wires. Think ahead & give yourself some access panels for when/if you need to make repairs.

Attaching things to your earthbag walls can be done in several ways:

1.) As you're building your walls, you can lay baling wire, threaded rod, or strong twine between the bags so they dangle on both the inside and the outside. You can then tie in your attachments.

2.) You should be able to gently tap stakes through your walls if you did a good job with your fill. This might be easier when your bags are semi-dry, but you usually can do it between bags (remember the barbed wire) if your stakes are flat.

3.) You can selectively

use "gringo blocks" (wooden blocks the same size as

tamped earthbags) to secure heavy things like door

frames, counters, cabinets, and the like. If you do,

drive nails top & bottom to wrap the barbed wire

around as you're working on that course so you can

secure the blocks in place and help prevent them

from pulling out if your counter or cabinet or

whatever ends up bearing too much weight. Worst

case, you want it

to fail, not the wall that it's attached to.

Framed Construction:

Some jurisdictions

(state, county, city) have proscriptive regulations

against non-conventional construction materials

& methods. If you want to use earthbags, one

possible way around this is to build a traditional

framed structure and use the bags to fill in the

walls between the studs.

Benefits include savings

on cost over a traditional frame building, superb

insulation value, and maintaining control over your

materials (bearing in mind that some "approved"

building materials on the market may later be found

to outgas or aggravate allergies). Plumbing, wiring,

and attachments will be straightforward and won't

require creative measures as is common with

earthbags alone.

Since earthbags are 12"

wide, your frame components (top & bottom

plates, studs, etc.) should be wider than

traditional 2x4s or 2x6s, meaning more wood. Because

of earthbags' superior load-bearing quality, you

could probably use 24" spacing between your studs

instead of the traditional 16". Obviously, you'll

have trouble tamping your bags as they rise towards

your top plate (no room for the tamper handle).

Overall, a hybrid framed/earthbag structure will be more costly than one constructed with earthbags alone. However, It can stand to be less costly than a traditional framed structure. It will be easier to get permits (and homeowners' insurance) for a hybrid as opposed to a structure made solely of earthbags. And if you're hiring a contractor to do the work, they'll understand the concepts.

This might be about the extent of how much you want to involve traditional contractors with earthbag construction, though. A good contractor will be understandably wary about possible code violations & potential liability concerns. You, for your part, should be wary about someone building your house using alternative materials & materials that they might not understand or fail to exercise proper care. Our advice? Do it yourself so you know it's done right.

Again, this is just an introduction. None of this is not meant to be a comprehensive guide to earthbag building. If you're serious, do your research. There are great resources in the library and on the Web. By all means, do experiment, seek out advice from people who're knowledgeable about both earthbag and conventional construction, and please be safe.

copyright � 2009-2020 New Mexico Dirtbags

| New Mexico Dirtbags Albuquerque, NM 87106 (505) 750-3478 (DIRT) |