|

Erosion control & slope stabilization

Landslides,

Debris

flows, Creep, Slumps

This is just an introduction and an overview. There are

many things that a property owner or a general contractor

can do to reduce the chance of earth movement before it

happens, or to mitigate it after the fact.

If you're looking for some ideas to deal with water

erosion (ocean waves, rivers & streams

washing away or undercutting banks, levees, etc.) then you

might want to also look at our flood

control page.

Beyond these pages, we encourage you to expand your

search. There are great websites (especially government

sites) and books that offer a much more comprehensive

treatment of a complex topic than we do. But

there's no substitute for getting a qualified &

licensed engineer, architect, or geologist on site,

especially if safety or protection of property is

at stake.

Slope failure (or "mass wasting") can be described as

downslope movement of soil or rock debris. It can be slow

and gradual (creep), or sudden (slumps, debris flows, and

landslides).

Gravity is always at work on a slope. A "stable

slope" can be broadly described as being about

30 degrees or less (angle of repose) and possessing a

solid footing at its bottom. A slope of more than 30 degrees can be stable, and

one less than that can be unstable. Factors like a lack of

vegetation, soil composition & compaction, moisture,

surface friction, presence of rocks or boulders, etc. can

all quickly contribute to slow movement ("creep") or

sudden collapse.

bottom. A slope of more than 30 degrees can be stable, and

one less than that can be unstable. Factors like a lack of

vegetation, soil composition & compaction, moisture,

surface friction, presence of rocks or boulders, etc. can

all quickly contribute to slow movement ("creep") or

sudden collapse.

There are a variety of other things that can make a slope

unstable or cause it to move. Water results in saturated

soil and rapid erosion. This is the most common cause of

failure. Heavy rains, a backed-up culvert, a broken

underground water main can all contribute to a slope

failing within hours, through lubrication and liquifaction

of the soil and by increasing the weight of the soil

dramatically.

Fires can be disastrous to slope stability. They burn off

the vegetation and kill the roots that hold the soil

together. Enhanced flooding may result because the heat

from the blaze can scorch the bare soil to a hard glaze

("burn scar") that rainfall just sheets off - resulting in

fierce flow volume & velocity.

Other causes of slope failure can include heaving

(the cycles of wetting &

drying, especially with clay-rich soils), or

freezing and thawing; earthquakes;

vibration from heavy nearby construction or

traffic; and overloading the top

of the slope, such as building a house or a

high-traffic road too close to the

edge.

Among man-made causes, backcutting the foot of the

slope (or failing to

ensure its adequate drainage, allowing it to

become oversaturated &

unstable) is perhaps the most common. It's what we

do when we build roads or houses at the bottom of a slope,

and it's like pulling an orange from the bottom of a pile

in the supermarket's produce section. Equally dangerous is

overloading the top of the slope (such as building houses,

condos, or roads) on the edge; their weight puts downward

pressure on the slope, and they contribute significantly

to rainwater runoff which can accelerate erosion.

Recognizing

instability:

Signs that a slope might be unstable or creeping include

cracks in asphalt or cement paving, leaning trees,

fenceposts, or utility poles (either towards or away from

the hillside); offset fence lines; and changes in

vegetation (suggesting the new presence of water).

If there's a structure (on the slope, at its top, or at

its bottom), signs of movement can include cracks or soil

moving away from the foundations, sticking doors and

windows, cracking concrete floors, sunken or down-dropped

spots in roads & driveways, broken water pipes, and

noticeable movement or separation of decks & patios in

relationship to the building.

Steps

to take:

Again, this page is just an overview. In some cases, it

can be a quick fix. In other cases, you can spend a lot of

time, effort, and money, including securing the services

of a professional engineer or geologist. And sometimes you

might be flogging a dead horse - the conditions may just

be impossible (see above photo). Some things to look into

doing can include:

- eliminating or redirecting sources of water that might

be overly saturating the soil;

- covering the slope with geotextile material;

- planting vegetation;

- terracing or benching the slope;

- installing lateral french drains or culverts;

- minimizing or eliminating elements that cause surface

erosion;

- using straw wattles or bales to break the velocity of

runoff & to catch sediment;

- stabilizing the slope with shotcrete or gunite, and

covering with wire mesh.

Equally important are redirecting flow sources to cut

down erosion & soil saturation, and stabilizing &

reinforcing the foot of the slope with retaining walls.

These are where sandbags can be helpful.

Overhangs:

On steep slopes here in the Southwest, the differentiated

strata that's so common can often result in hard rock

that's underlain by easily eroded softer rock. This can

result in a slope face in which hard rocks are hanging

over a concave face that's been eroded away. A vertical prop

wall can be built with sandbags, filling in the

concavity, and reaching up to support the overhanging

rocks. (Think of a filling in a tooth cavity - same

concept.) This can be secured in place with fencing, and

will help to prevent further erosion to the softer

underlying rock. Overhangs:

On steep slopes here in the Southwest, the differentiated

strata that's so common can often result in hard rock

that's underlain by easily eroded softer rock. This can

result in a slope face in which hard rocks are hanging

over a concave face that's been eroded away. A vertical prop

wall can be built with sandbags, filling in the

concavity, and reaching up to support the overhanging

rocks. (Think of a filling in a tooth cavity - same

concept.) This can be secured in place with fencing, and

will help to prevent further erosion to the softer

underlying rock.

As with all permanent placements of polypropylene bags,

the bags need to be covered from the sun or plastered

(mud's fine, so long as it doesn't wash away; geotextile

fabric or shotcrete is better) so UV rays don't cause the

bags to disintegrate. The 1600 hours that our bags are

treated for is good for only a couple of months, at best.

If moisture isn't a problem, burlap bags might be your

best bet. A more expensive (but higher insurance)

alternative would be to use premium bags, such as our

4-year heavy-duty black polypropylene bags or polyethylene

Durabags.

After

collapse:

If it's safe to do so, the priority should be to prevent

any further sliding or damage as much as possible. If

there's a building, road, or stream immediately downslope,

you can stack sandbags and try to create a wall or barrier

that will contain or divert mud, rocks, and any further

collapse of soil. If it's raining, doing this right away

will help prevent the fallen material from liquifying

& spreading, especially desirable if - again - there's

a house or a road.

If there's any significant water flow on the upper part

of the slope that might aggravate further collapse, it

might be possible to divert or redirect it with a sandbag

check dam (see below). Odds are, however, that it's best

at this point to evacuate & come back in a few days

with heavy machinery.

As mentioned above, support can be provided to

overhanging rocks that are at risk of coming down with a

vertical prop wall of sandbags, and eroded concavities can

be filled in with bags to help stabilize the slope &

prevent further erosion .

Diverting

and

redirecting flows:

If slopes have any purpose, it's to transport water

downhill to drainage systems (creeks, arroyos, rivers). It

can be concentrated (like in a gully) or it can be a sheet

of water covering the entire slope. Such surface flows can

be diverted by channeling the flow sideways to what can be

a "safe" drainage. Safe drainage can include pipes,

gullies, and swales (that allow backed-up water to seep

through absorbant soil) which are away from the slope

that's being protected.

Diversion methods can include building channels with

rocks or sandbags, elevated berms, check dams (see photo)

and/or channels with rocks or sandbags. Berms and check

dams generally don't need to be any more than two feet

high, and don't necessarily require any digging (though a

bonding trench will help to prevent the bags from washing

away in large flows). Placing barbed wire between the

layers of bags, and/or covering them with wire mesh can

make them solid & resistant to collapse. Covering them

with earth, concrete, stucco, or a basic earth plaster

(clay-rich dirt, sand, and straw) will do the same, and

protect the bags from the sun's UV rays & abrasive

deterioration. If using bags, burlap bags may be a better

choice.

On the other hand, it's worth noting that slowing down

runoff can lead to ponding, which gives water a chance to

seep into the soil and undermining your barrier. Sandbags

that aren't sealed won't provide a 100% waterproof

barrier; water will seep through them, which helps prevent

ponding. It's a trade off, and depends on if you're

looking at a temporary or a permanent fix. Sealing your

bag barrier - say, with plastic sheeting - will require

some forethought about how you're going to deal with any

possible standing water issues.

In addition to dealing with water flow, another source of

concern is mud and debris flows. These can be disastrous -

not only because of their destructive weight, but because

they can precipitate a domino effect when they rush down a

slope that's already saturated. The best you can hope for

is prevention. If your check dams are successful at

catching them and retaining them, you're going to want to

clean them out after the storm.

Stabilizing

the

base:

People like to build roads, houses, and patios at the

base of hills and slopes, and tidy them up & maximize

the real estate by removing the wedge. Doing this,

however, weakens the slope - because the slope

exerts downsloping pressure (even if it's not actively "on

the move", or "creeping"), this is where the weight of the

slope is concentrated.

A well-built retaining wall (toewall) at the base of the

slope should follow the

A well-built retaining wall (toewall) at the base of the

slope should follow the

line (angle) of the slope as much as possible.

Where is the direction of force

coming from? The retaining wall should meet this,

and smoothly transfer the

downward weight of the slope. It should be wider

at its base, narrowing as it

rises, and lean solidly against the slope. Even

better would be excavating

the base of the slope and building the retaining

wall into it.

Sandbags are well-suited for this; they're

portable, easy to work with, and

can be solidly tamped into place. Again, strips of

4-point barbed wire can be

placed between the courses, locking the bags

together. Since UV rays tend to break the polypropylene

fabric down over time, it's a good idea to plaster or

stucco the bags after the wall is built.

Don't overlook the importance of dealing with drainage.

If hillside saturation is an issue, one approach

is "weep holes" in your wall - spaces between bags

every three feet or so, downward-sloping if possible.

While a polypropylene sandbag retaining wall won't

necessarily wick up water, failing to providing an outlet

for it as it backs up behind the bags can supersaturate

& weaken the surrounding soil. Or, if the soil behind

the bags is rich in clay, it can cause that soil to swell

& expand, pushing your bags out, ruining your wall at

the least and possibly resulting in total slope

failure.

Working

with sandbags:

Sandbags come in two basic materials. Burlap is subject

to rot and is attractive to insects and rodents.

Polypropylene is rip-proof and water resistant, but prone

to deterioration in the sun (our poly bags are treated

with 1600 hour UV inhibitors, which in New Mexico summers

gives them a life span of only a couple of months). Either

material will last longer if sealed with stucco or cement.

A basic earth plaster can be made on-site out of clay-rich

dirt, sand, and water (a little straw will give it

strength). On a summer day, it will bake in the sun and

may last for years with a little maintenance. If your

project is temporary, you can simply cover the bags with

tarps or shovel some dirt over them to keep the sun off.

It's not a bad idea to pick through or sift your dirt

before filling your sandbags, removing sharp twigs &

branches, as well as root balls and clusters (which can

sprout & burst through the bag). Bags are generally

filled 1/2 way, then tied off & laid horizontally. The

opening is folded under as the bag is laid, and the bag is

shaken to distribute the contents equally. A hand tamper

is then used to compact them.

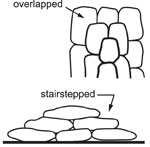

As they're being laid, the bags should be overlapped and

butted together (see image). If they're being subjected to

lateral force (such as a check dam), the basic rule of

thumb is that the base should be 3 times the height, which

calls for a pyramid construction.

Depending on your fill material, a standard sandbag (14"

x 26") will weigh about 25-30 lbs after being half filled.

This means that every 65 to 80 bags will give you a ton

(2,000 lbs) of reinforcement. One average person can

fill, tie off, place & tamp 20 bags per hour. Several

people, setting up a production line, can crank out 100 or

more bags per hour (see our bag

filler). If it's a big job, we can bring our sandbag

machine out to your site, which is capable of cranking out

over 800 bags per hour.

Burritos:

If you have the means to deploy them (they can be large

& heavy), you can construct what we call

"sandbag burritos". They're essentially quick-and-dirty

cylindrical gabions holding filled sandbags that take less

than 10 minutes to construct.

Roll out some 6-foot chain link fence, then cut out a

3-foot wide section. Next, lay a number of filled sandbags

on it (say, two vertical rows of 3 or 4 sandbags), then

roll it up & fasten the edges and the ends with hog

rings. Six 50-lb sandbags gives you a 300-lb, 6'L x 2'

round burrito. Eight 50-lb sandbags will give you 400 lbs.

Twelve 50# sandbags will give you 600 lbs. You get the

idea.

The chain link allows you to link the burritos together

after they're placed. Utilizing higher-quality

sandbags and/or covering the burritos with dirt (so

UV exposure doesn't cause the bags to disintegrate) will

help ensure long life. Even better might be to use our snake

bags.

Deploying burritos isn't always easy because of their

weight and because erosion sites tend to be steep, uneven

and unstable. Being cylindrical, they do roll off a steep

edge nicely; the trick is making them stop rolling where

you want them. Hooking up premeasured chain to them with a

solid belay before rolling them over the edge helps make

them stop where you want them; then hammering in a few

fence stakes below them will keep them put. If your

conditions call for them, they're easy, inexpensive, and

far more effective than just using individual sandbags. If

you like, we can supply them to you pre-assembled to your

specs; write or give us a call.

In many areas, you may need a permit to build retaining

walls. If you plan to file a claim with your property

insurance, you might have it rejected unless you had an

engineer or a licensed professional involved before

you built.

In times of disaster, bags can sometimes be acquired from

your local fire station or emergency response authorities

- but they may be limited in number (some have told us

that they've encountered limits of 10 to 20 bags per

household).

For farmers & ranchers, businesses, government &

tribal agencies, and anyone else, we can provide bags in

any quantity, from one to 100,000 (larger quantities need

to be pre-ordered). We don't stop at just selling them to

you - if necessary, we'll do whatever it takes to get your

bags to where you need them, and free you up to worry

about other things. Visit our shopping

page or contact us for prices & options.

For more in-depth information about controlling erosion,

you can download a 64-page USFS booklet here

(pdf). Also, we highly recommend An

Introduction to Erosion Control from the Quivira

Coalition in Santa Fe, available for download here

(also in pdf format).

Use this information at your own risk. No one

associated with New Mexico Dirtbags will have liability

for any loss, damage or injury resulting from the use of

any information, recommendations, or claims found on this

or any other page at this site. All information,

advice, suggestions and recommendations are offered in

"good faith". Likewise, New Mexico Dirtbags, its

principals and its employees, will in no way be held

liable for any loss, damage, or injury arising from the

use of any of the products sold or provided. Purchasers

and users of products, information, and advice made

available by New Mexico Dirtbags are hereby notified that

they are responsible for conducting their own research,

for taking all reasonable precautions, and for assuming

full responsibility.

|